- 5 state behavioral health policy updates

- Oregon’s anti-consolidation bill tested by physician contract switch-up

- Mass General Brigham, Dana-Farber to coordinate on split: Boston Globe

- How AI-enabled early detection is redefining preventive care

- Medical device maker Stryker hit with cyberattack

- New York university to launch dental school

- Aetna to pay $118M to resolve Medicare Advantage upcoding allegations

- Fraud lawsuits against Erlanger can proceed, judge rules

- Medical debt linked to deferred dental care: Study

- FDA launches single adverse event platform

- Riverside Health taps new system finance leader, hospital president

- Medicare beneficiaries may pay more amid insurer acquisitions of PBMs: Study

- Medicare beneficiaries may pay more amid insurer acquisitions of PBMs: Study

- Virginia Mason Franciscan exec heads to Providence

- IU Health bets on ‘big, one-time endeavors’ for the future

- IU Health bets on ‘big, one-time endeavors’ for the future

- Atrium Health Wake Forest Baptist taps hospital president

- ADHA targets professional autonomy in new strategic plan: 5 notes

- Duke University Health System files CON for $6.4M ASC

- Ohio dental practice to permanently close

- 3 health systems outsourcing RCM functions

- A flurry of noncompete updates in Q1

- Specialty1 Partners continues 2026 growth with new joint venture

- The CMS loophole shrinking ASC access: Inside ASCA advocacy

- CMS imposes equipment supplier moratorium; 3 sentenced to prison in fraud cases

- Guidelight names chief growth officer

- ‘A delta in opportunity’: The savings independent ASCs are leaving on the table

- Despite insurers' expense pains, Tenet Healthcare is securing healthy commercial rates through 2027

- Nebraska Medicine’s $99.3M center to expand behavioral health services

- FDA approves 1st treatment for cerebral folate deficiency tied to autistic features

- 8 health system rating downgrades

- The looming impact of site-neutral payments on ASCs

- Dental industry headed for consolidation shift amid DSO financial woes: 4 notes

- Why this anesthesia leader says stipends are here to stay

- Northwestern Medicine opens expanded outpatient center

- Meet the ASC industry’s ‘alternative to the traditional MSO’

- University of Minnesota dental clinic closes over financial challenges

- Study Links State Taxes to COVID Lockdown Decisions

- Hospital expenses grew twice as fast as prices in 2025: 4 AHA findings

- Aetna to pay $117.7M to settle Medicare Advantage upcoding allegations: DOJ

- Connecticut fines debt collector $100K for calls to hospital emergency line

- ADA names Dr. Nader Nadershahi as executive director

- Connecticut health system strikes RCM partnership

- Stryker hit by international cyberattack linked to pro-Iran group

- AHA: Hospitals' total expenses rose by 7.5% in 2025

- AstraZeneca recruits Joshua Jackson, Philadelphia Flyers’ Gritty to cancer screening push

- As Lilly flourishes in Q4, peer projections signal looming sector slowdown in 2026

- FDA May Allow Some Flavored Vapes Aimed at Adults

- Dark Sweet Cherries May Help Slow Aggressive Breast Cancer, Mouse Study Suggests

- FDA Approves Leucovorin for Rare Brain Disorder, Not Autism

- Joint Economic Committee report: Medicare Advantage overpayments drive up Part B premiums

- Veeva shells out $100M for Ostro and its AI chat tool for pharma brand engagement

- Lilly beefs up oral GLP-1 capacity with $3B manufacturing pledge in China

- UCB's Bimzelx continues winning streak with victory over AbbVie's Skyrizi

- Lowering Parents' Stress Can Reduce Risk Of Childhood Obesity

- Multilingualism Might Not Aid Brain Aging, Researcher Argues

- 15-Year Study Shows Sharp Rise in Depression Among U.S. College Students

- Repealing Motorcycle Helmet Laws Leads to More Severe Crashes, Millions in Added Treatment Costs

- Why Childhood Cavities May Predict Adult Heart Disease

- Physical Therapy Costs Vary Widely In U.S., Study Finds

- J&J's Joaquin Duato joins $30M CEO pay club with 30% compensation boost for 2025

- Cosmetic Surgery Investigation Prompts Warnings for Patients, and a Push for Tighter Safety Standards

- Primary Care Is in Trouble. So Doctors Band Together To Boost Their Market Power.

- Skyhawk taps Teva alum to steer commercial path, while Santhera names new CCO to grow DMD sales

- Driving the news at HIMSS26: Verily, Samsung ink collaboration; Meditech's latest AI solutions

- Minnesota to give $5M in restitution to patients of shuttered dental office

- Colorado hospitals, advocates launch youth mental health coalition

- Pennsylvania hospital CFO on life after bankruptcy: ‘You’ve got to hold the line’

- Medicare allegedly paid $15M+ for ED services tied to non-ED sites: Report

- Climate warming could increase anxiety, depression: Study

- Sutter Health boosts operating margin to 2.6% in 2025

- Remarks at the Institute of International Bankers 2026 Annual Washington Conference

- Fostering Regulatory Harmony Between the SEC and CFTC

- Only 4 states satisfy over 50% of mental health workforce needs: Report

- Here's where hospital markets are the most concentrated

- A look at how CVS is leaning on 'agentic twins' in developing consumer tech

- Bancos, primera línea de batalla contra los fraudes financieros a adultos mayores

- Inside Grand Mental Health’s tech-enabled crisis response model

- Sandoz to set up standalone biosimilars unit as it eyes upcoming 'golden decade' of patent losses

- Indiana syringe services face ID requirement, restrictions

- AbbVie's Robert Michael earns hefty pay bump to $32.5M in 2nd year as CEO

- NYU Stern report calls for private equity reforms to safeguard quality of care

- Remarks at the International Bar Association’s 24th Annual International Conference on Private Investment Funds

- Raw Oysters and Clams Recalled After Norovirus-Like Illness Outbreak in Washington

- Mammograms May Also Reveal Hidden Heart Disease Risk, Study Finds

- Chile Becomes First Country in the Americas To Eliminate Leprosy

- Going Abroad? CDC Warns Travelers About Polio Risk in Several Countries

- Listen to the Latest ‘KFF Health News Minute’

- The Fierce Healthcare team on the Fierce 15 of 2026

- Más niños llegan a salas de emergencias con dolor de muelas. Los recortes de Trump y la lucha anti flúor de RFK Jr. no ayudan

- Centene's stock falls as CEO London outlines ongoing ACA headwinds

- AI-fueled misdiagnoses, rural care barriers are 2026's top patient safety threats: ECRI

- Patients want price transparency, e-commerce experience from pharma DTP platforms: survey

- Carrum Health teams up with Virta Health on a comprehensive weight loss solution

- Leerink questions whether BioNTech can thrive without their 'founders' insight' as stock drops

- Novo Nordisk's US headquarters under fire in latest FDA warning letter

- Filana leaves Cassava roots behind amid branch into epilepsy

- Nearly Half of U.S. Kids Lack Adequate Sleep, Survey Shows

- Trump Caused Immediate Decrease in Acetaminophen Rx's For Pregnant Women, Study Finds

- Students Spend A Third Of Their School Day On Their Smartphone, Study Says

- Daily Multivitamins Slow Aging, Clinical Trial Finds

- Stress of Pregnancy Complications Might Impact Future Heart Health, Study Says

- Approved IV Drug, Gazvya, Reduces Lupus Symptoms, Clinical Trial Finds

- CSL telegraphs 300 new hires as it breaks ground on $1.5B plasma-based medicine plant near Chicago

- Banks Are Becoming Bulwarks Against Scams for Vulnerable Seniors

- More Kids Are in ERs for Tooth Pain. Trump Cuts and RFK Jr.’s Anti-Fluoride Fight Aren’t Helping.

- FDA approves leucovorin for ultrarare cerebral folate deficiency subset without clinical trial

- BioNTech's CEO, CMO prep departure to set up next-gen mRNA company

- 12 new behavioral health sites to know

- HIMSS26: Samsung, b.well partner to 'kill the clipboard,' aligning with a key CMS goal

- HIMSS26: Epic expands AI roadmap, previews Factory to build and orchestrate AI agents

- A $21M farewell: Emma Walmsley lands nearly 50% pay hike in final year as GSK chief

- Remarks at the 45th Annual Small Business Forum

- Founders, Funders, and Forty-Five Forums: Remarks at the 45th Annual Small Business Forum

- Remarks at the 45th Annual Small Business Forum

- Leapfrog ordered to remove safety grade for 5 Tenet hospitals

- FDA unveils 4th revision of draft guidance for looser biosimilar testing requirements

- 'Fibermaxxing' Trend Encourages People To Eat More Fiber

- Lilly rewards CEO David Ricks with $36.7M pay package for 2025, fueled by GLP-1 success

- That Stressful Person in Your Life Might Be Aging You Faster, Study Finds

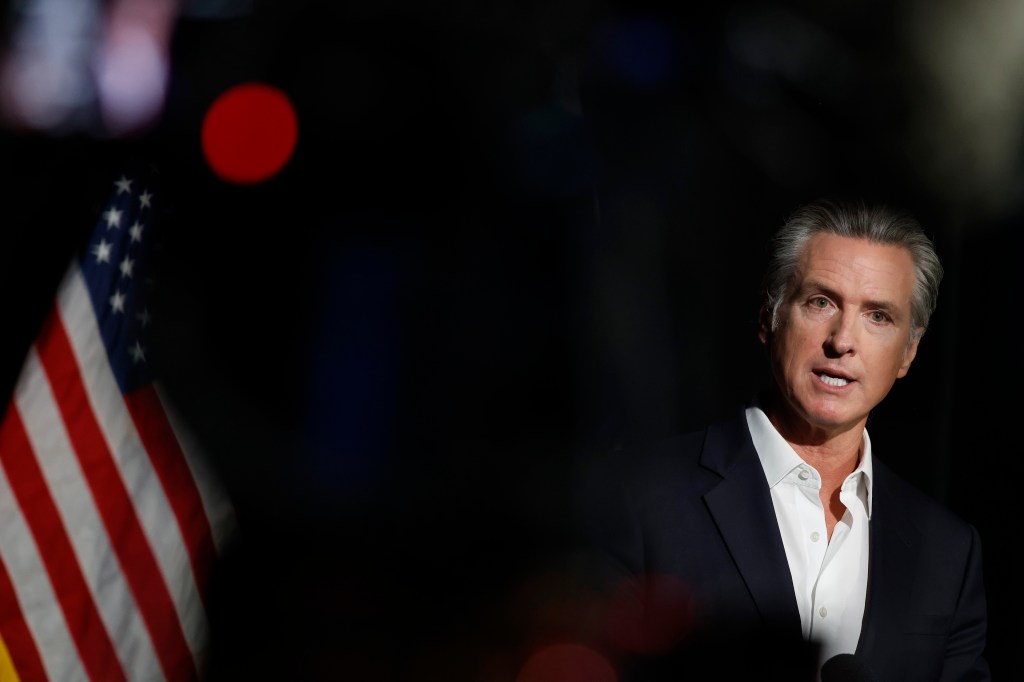

- Newsom se enfrenta a Trump y RFK Jr. por la salud pública

- Infant Bath Seats Sold on Amazon Recalled Due To Tipping Hazard

- FDA Vaccine Chief Dr. Vinay Prasad Exiting Role

- Spruce hooks a commercial chief to prep for rare disease launch

- Hims & Hers makes deal with Novo Nordisk as it shifts obesity strategy

- Fierce Healthcare highlights Fierce 15 of 2026 honorees at NYSE

- Universal Health Services to acquire Talkspace in $835M deal to build out virtual behavioral health

- Florida no amplió Medicaid, pero igual algunos legisladores quieren imponer requisitos de trabajo

- Novo and Hims make nice, striking deal to sell Ozempic, Wegovy on Hims' telehealth platform

- Sotyktu, take 2: BMS' first-in-class pill gains FDA nod to treat psoriatic arthritis

- 'SNL' pokes fun at mysteries of Amgen's Otezla for plaque psoriasis

- Weighted Vests Help Keep Bones Strong — But Only If Seniors Stay Active

- Small Drop In Measles Vaccinations Tied to Big Jump In Cases

- UV Air Filters Cut Airborne Asthma Triggers, Study Finds

- Many Seniors Gain Physical, Mental Fitness As They Age, Study Finds

- Common Drug Class, Anticholinergics, Shows Links to Heart Risk — Are You Taking One?

- Illicit Drugs Raise Stroke Risk, Even for Younger Adults

- Florida Hasn’t Expanded Medicaid. Lawmakers Want To Add Work Requirements Anyway.

- Omada Health swings to a profit in Q4, offers new GLP-1 cash-pay option for employers

- Most Americans Say They Don’t Trust Driverless Cars — Here’s Why

- Can The Critters in Your Mouth Cause or Cure Disease?

- KFF: A look at Part D enrollment trends for 2026

- Healthcare Dealmakers—Hims & Hers goes international with Eucalyptus purchase, Humana's CenterWell buys MaxHealth and more

- Some Patients Keep Weight off With Fewer GLP-1 Injections, Study Finds

- RFK Jr. Urges Medical Schools To Add More Nutrition Training

- Sixth Measles Case Confirmed in New Mexico Jail

- Community Health System selling 4 Arkansas hospitals to Freeman Health System for $112M

- Philips unveils Rembra CT for acute and high-demand imaging environments

- Philips unveils Rembra CT for acute and high-demand imaging environments

- 45,000 Halo Magic Sleepsuits For Babies Recalled Over Choking Risk

I featured Michigan's poor treatment of Nurse Practitioners on MHF video earlier this year.

It's also the issue championed by bill sponsor and fourth MHF 2025 Defender Award Nominee.

This week, Mackinac Center lays out legal and health benefits from changing Michigan law.

https://www.mackinac.org/blog/2025/michigan-would-benefit-from-independent-nurse-practitioners

Michigan would benefit from independent nurse practitioners

More than 30 states allow the practice

Warren Anderson | December 4, 2025

The Michigan Legislature is considering bills to allow nurse practitioners to be independent operators, which they currently can do in most states. Recent research suggests this would lead to fewer malpractice lawsuits, better care that leads to hospital stays being shorter, and fewer preventable deaths.

The nurse practitioner profession began in the 1960s. Nurses had to earn at least a Master of Science in nursing, pass a national licensing exam and obtain a state license. All states initially required nurse practitioners to work under the supervision of a licensed physician. But now more than 30 states allow these medical professionals to operate on their own, which is known as full practice authority.

Some interests in the established medical field, such as the American Medical Association, opposes empowering nurse practitioners to work on their own. Naysayers cite potential poorer care as a reason to oppose such laws. Recently published scholarship, however, undermines this concern.

Sara Markowitz and Andrew Smith of Emory University and the Food and Drug Administration, respectively, analyzed states that changed their laws to allow full practice authority. Twenty states made such a change from 1998 to 2019. The authors looked at malpractice cases to test the impact of these laws. If patient care worsened, malpractice cases should increase.

Markowitz and Smith found that letting nurse practitioners practice independently had no impact on their own malpractice payments. Further, malpractice payouts for physicians declined by a little more than 20%. The number of safety and drug violations committed by medical professionals did not change for the worse. These findings suggest that enabling full practice for nurse practitioners does not result in poorer patient care.

The fact that physicians experienced fewer malpractice cases is possibly due to liability laws. Doctors could be held liable in some cases for an error by one of their supervised nurse practitioners, even if the physician had no contact with the patient. When these nurses become directly responsible for their actions and physicians no longer responsible for them, overall malpractice claims fell. The change does not directly show that full practice authority laws improved levels of care, but it does suggest that they reduce the type of harmful actions that typically lead to claims of malpractice.

Benjamin McMichael of the University of Alabama tested the impact of full-practice laws on the quality of care in a different way. He used data on nearly every hospital discharge in 22 states, including Michigan, from 2010 to 2019. Ten of these states enacted full-practice laws during this time, enabling McMichael to test the effects of changing state policy on medical outcomes. He looked at outcomes related to which hospital admissions could have been avoided with better outpatient care, the type that nurse practitioners often provide.

McMichael found that full-practice laws were associated with a roughly 5% decline in hospitalizations. This has large cumulative effects: Hospital stays declined overall by about 108 days per 100,000 people. For Michigan, that would mean roughly 11,000 fewer stays in hospitals, making medical care cheaper and less disruptive for consumers and freeing doctors’ time and resources for more serious medical issues.

In a separate paper, McMichael assessed the impact that these laws have on “health care amenable deaths,” or “premature death(s) from causes that should not occur in the presence of timely and effective health care.” Looking at data across the United States from 2005 and 2019, McMichael found that allowing nurse practitioners greater freedom to practice reduced amenable deaths by 12 per 100,000 individuals, with the largest impact on underserved, rural areas. This makes sense as nurse practitioners often establish practices in places where health care is in short supply.

If Michigan allows nurse practitioners to offer medical services on their own, the state would simply be mirroring what most states have done. Studies on the impacts of this legal change suggest that malpractice suits would decline, hospital stays would drop because of better earlier medical treatment, and unnecessary deaths would decrease. The Legislature should follow the lead of other states and allow better and more accessible medical care for Michiganders.

Mackinac Center's Nurse Practitioner (NP) article last month focused on the economic and policy aspects of full practice authority.

https://www.mackinac.org/blog/2025/let-nurse-practitioners-do-their-jobs

Let nurse practitioners do their jobs

Michigan is one of only 11 states severely restricting their practice

November 24, 2025

Michigan's limits on nurse practitioners are a prime example of economist Thomas Sowell’s maxim that “There are no solutions, only trade-offs.” These are highly trained nurses with graduate degrees who can diagnose illnesses, prescribe medications, and provide high-quality care. Research conducted over many decades shows that nurse practitioners perform as well as physicians in most cases, that their patients are equally satisfied, and that their services cost less.

Yet the state sharply limits nurse practitioners, providing little or no benefit to public health while leaving patients with higher costs, fewer options, and less freedom.

Michigan is 14th in the nation for the number of active primary care providers per capita. That's great, but providers are not dispersed equally. Some 2.7 million people live in Michigan’s 256 health professional shortage areas. When those people get sick, there aren't enough primary health care providers to help them.

Yet Michigan is one of only 11 states that still require nurse practitioners to be under the direct supervision of a physician, according to the American Association of Nurse Practitioners. State law says they can't do their jobs without paying a doctor to “supervise” them. That's not because patients are safer under this arrangement; they aren't. It's because the state gives doctors a near-monopoly on certain kinds of care. The result is fewer providers, longer wait times and higher costs for everyone else.

House Bill 4399, introduced by Rep. David Prestin, R-Cedar River, and Senate Bill 268, sponsored by Sen. Jeff Irwin, D-Ann Arbor, would change that. The bipartisan proposals would let nurse practitioners practice independently, just as they can in most states.

In practice, Michigan's supervision requirement means many nurse practitioners must pay thousands of dollars each year to a doctor for what is often little more than a signature on paperwork. This doesn't change how patients are treated, but it drives up costs and discourages nurses from opening clinics, especially in underserved areas.

The real beneficiaries of these restrictions are doctors who collect fees for “oversight.” That's why physician associations like the American Medical Association and the Michigan State Medical Society spend heavily to maintain the status quo. The AMA admits it has poured millions of dollars into advertising and lobbying campaigns to stop nurse practitioners from gaining full practice authority.

This is bad policy and bad economics. Independent studies consistently find that restrictive laws lead to worse health outcomes and higher prices. One analysis found insurers paid 3% to 16% more for basic child wellness visits in states with tight restrictions on nurse practitioners. Another study found nurse practitioners were far more likely to relocate to states that allow full practice authority. And a 2022 study found parents rated their children’s health higher in states that let nurse practitioners work without supervision.

If lawmakers truly want to make health care more affordable and accessible, the evidence is clear: They should loosen the reins. Michigan’s rules don't protect patients — they protect incumbents. They also leave rural and low-income communities with fewer health care options.

The Michigan bills have a bipartisan group of co-sponsors and are supported by nursing associations across the state. Predictably, the physician lobby is opposed. Lawmakers should look past the politics and focus on what's best for Michigan residents.

Government shouldn’t stand in the way of qualified professionals doing their jobs. There are no perfect outcomes, but this trade-off is an easy one: Let nurse practitioners work to the full extent of their training, expand access to care, and bring a little common sense back to Michigan’s health care laws.

David Mitchell is the Distinguished Professor of Political Economy and the director of the Institute for the Study of Political Economy at Ball State University. Jarrett Skorup is the vice president of marketing and communications at the Mackinac Center for Public Policy.

Get MHF Insights

News and tips for your healthcare freedom.

We never spam you. One-step unsubscribe.