Are you a registered organ donor?

After attending this May 26 CE event by the Association of American Physicians and Surgeons, I was glad I had reconsidered being registered. Dr. Klessig explores the implications for individual rights, US, and state health policy, following her documentation of the current facts and ethics of organ donation:

- Tissue donation

- Living donation

- Forced organ harvesting

- Organ trafficking

- Donation after "Brain death"

- Donation after circulatory death

I highly recommend watching the video.

< https://rumble.com/v2q5l2g-the-dark-side-of-organ-harvesting-heidi-klessig-md.html>

SLIDES and RESOURCES

The slides (including links to additional handouts) from the presentation can be viewed at: https://drive.google.com/drive/folders/1lPqckImZ-WAzRko0IRL6R3PcQA_HwN7Y?usp=sharing

Please be sure to visit Dr. Klessig's website at:

https://www.respectforhumanlife.com/

Organ donation is a huge area - I believe crowd-sourcing is essential to truly understand it. After that, we can have a huge impact through state health policy.

To start - there's a ton of history. Even in the past 30 years, a lot has changed.

by | Jun 1, 2023When I took a Gift of Life class back in the 1990s, the principles seemed sound. I displayed the pin with those from Nurses Christian Fellowship and Right to Life.

Twenty years later, Michigan passed the bill for free-standing organ procurement center. I felt uneasy about the loss of local connection, but at the time, I missed the implications of brain-death definitions.

Last week, I attended a continuing education (CE) event on organ donation, and the pieces fell into place. Organ donation has become a mix of the very good, and the truly unthinkable. Change comes from every direction.

In this article I share some items from the CE event, along with information from bill-tracking and Michigan-specific research.

Ethics of Organ Donation are all over the place

The ideal, of course, is living donation. The plan is for both patients to go home healthy when someone donates a kidney, for instance. Cadaver donation of tissues is also uncomplicated ethically for most people, because biologic, cardiac death is evident.

Ethical conflict entered when death was redefined from the biologic shutdown we all recognize, to brain death. This was driven by the desire to transplant organs that require near-continuous bloodflow. Money is a factor, because even in the US where sale is illegal, a body is worth $5 Million in processing charges.

But because circulation, temperature regulation, and other brain and body functions continue, more people are recognizing “brain death” as a legal fiction rather than medical fact.

Current Bills Change Michigan Organ Donation

Currently, Michigan law provides three ways for residents to make an anatomical gift, or donate organs. They may do so in their will; by communicating their wishes at the time of illness or injury; or through driver license procedures at the Secretary of State, who maintains the Donor Registry with access by Gift of Life.

Three bills now in the Michigan legislature would:

- Revise the Michigan Tax Code. This bill adds a donor registry checkbox to state tax returns, accompanied by an optional tax form to file for joining the donor registry; and directs the Treasury to give these forms to the Secretary of State.

- Revise the Public Health Code to add this tax filing method of donating organs.

- Revise the privacy section of the Revenue Act to allow an authorized person in Treasury to disclose donor registration schedules to the Secretary of State’s office, and to Gift of Life.

These bills passed the Michigan House on May 11, with very few opposing votes. (Pages 5-8 of the House Journal.) They are tie-barred, meaning they take effect only if all become law. They await further action in the Senate Health Policy Committee.

Bill Questions to ask

Practically speaking, are the Michigan departments of state and treasury competent to handle this added complexity? Most of us have an opinion about how well they handle our driver licenses and taxes.

My concern, though, is about increasing complexity in Michigan organ donation. It is already heavily layered with federal, state, and public-private bureaucracy that are difficult for individuals to navigate.

Most importantly, what will be the effect on individual rights? Efficient individual care is already a challenge in healthcare.

The bills do not address current problems in the organ donation system, such as whether organ harvesting may take priority over determining possibly-criminal cause of death.

Potentially opening the door to more problems, a Michigan bill last year shifted ultimate responsibility for determining cause of death from county medical examiners and attending physicians, to the MDHHS director. The bill passed the House and reached the floor of the Senate before the end of term. It’s likely to return this term.

Given all the moving parts and the importance of securing the individual right to life, Is now (or ever) the right time to add another layer of organ donation bureaucracy and healthcare records?

Getting removed from the Donor Registry

First, watch the language bias. The organ procurement system emphasizes the “right to donate.”

But the real right, as every survivor of COVID mandates knows, is the right to refuse.

With so much changing, it is impossible to know what the rules will be when it comes time to donate your organs. If the only ones you tell are your family, you’ll find it a lot easier to change your decision to fit new circumstances.

So if you are one of the 50% of Michigan residents who have registered for organ donation, and you’ve changed your mind, here are some tips from my experience.

Peeling the label off a driver’s license is easy. So is skipping the checkbox on the renewal form.

However, changing online records is the real kicker. Ever try to correct an error in your medical record?

Online information never really goes away – but in this case it’s important enough to try.

- Some say Gift of Life will assist with removing a name from the donor registry. However, when I called they said they aren’t allowed to check the list for names, and referred me to the secretary of state.

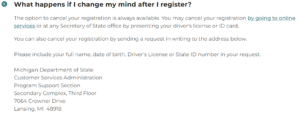

- The secretary of state website says, “The option to cancel your registration is always available.”

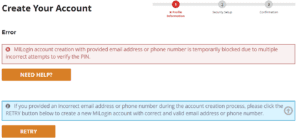

Unfortunately, “available” and “effective” are two different things.When I attempted to create an account online, it took 10 minutes for the email verification PIN to arrive. When it came, the system did not accept it. After three tries, it locked me out.- I’m dubious about the mail-in option, since no form is provided. (And why no email address??) So it looks like the local Secretary of State office is next.

Stay informed! Organ donation policy is constantly changing.

Don’t miss the full video of the continuing education event and the organ donation discussion in the MHF Community Forum!

There’s much more about the ethical issues and what you can do. Add your voice and experience to inform, while you learn from others. It’s important – and it’s free.

New research suggests that a subset of patients with psychiatric conditions such as schizophrenia may actually have autoimmune disease that attacks the brain.

The two women in this article were catatonic but not declared dead or at risk for "death by organ harvesting" - yet.

Fascinating from a clinical perspective, and it makes you wonder about the many poor souls who are kept homeless, incarcerated, or institutionalized by mental incapacity.

Too long to quote in full, but worth the read.

https://www.washingtonpost.com/wellness/2023/06/01/schizophrenia-autoimmune-lupus-psychiatry

By Richard Sima June 1, 2023 at 6:00 a.m. EDTThe young woman was catatonic, stuck at the nurses’ station — unmoving, unblinking and unknowing of where or who she was.

Her name was April Burrell.

Before she became a patient, April had been an outgoing, straight-A student majoring in accounting at the University of Maryland Eastern Shore. But after a traumatic event when she was 21, April suddenly developed psychosis and became lost in a constant state of visual and auditory hallucinations. The former high school valedictorian could no longer communicate, bathe or take care of herself.

April was diagnosed with a severe form of schizophrenia, an often devastating mental illness that affects approximately 1 percent of the global population and can drastically impair how patients behave and perceive reality.

“She was the first person I ever saw as a patient,” said Sander Markx, director of precision psychiatry at Columbia University, who was still a medical student in 2000 when he first encountered April. “She is, to this day, the sickest patient I’ve ever seen.”

It would be nearly two decades before their paths crossed again. But in 2018, another chance encounter led to several medical discoveries reminiscent of a scene from “Awakenings,” the famous book and movie inspired by the awakening of catatonic patients treated by the late neurologist and writer Oliver Sacks.

Markx and his colleagues discovered that although April’s illness was clinically indistinguishable from schizophrenia, she also had lupus, an underlying and treatable autoimmune condition that was attacking her brain.

After months of targeted treatments — and more than two decades trapped in her mind — April woke up.

“These are the forgotten souls. We’re not just improving the lives of these people, but we’re bringing them back from a place that I didn’t think they could come back from.”

— Sander MarkxThe awakening of April — and the successful treatment of other people with similar conditions — now stand to transform care for some of psychiatry’s sickest patients, many of whom are languishing in mental institutions.

Researchers working with the New York state mental health-care system have identified about 200 patients with autoimmune diseases, some institutionalized for years, who may be helped by the discovery.

And scientists around the world, including Germany and Britain, are conducting similar research, finding that underlying autoimmune and inflammatory processes may be more common in patients with a variety of psychiatric syndromes than previously believed.

Although the current research probably will help only a small subset of patients, the impact of the work is already beginning to reshape the practice of psychiatry and the way many cases of mental illness are diagnosed and treated.

“These are the forgotten souls,” said Markx. “We’re not just improving the lives of these people, but we’re bringing them back from a place that I didn’t think they could come back from.”

Losing April

Even as a teenager growing up in Baltimore, April showed signs of the college accounting student she would later become. She balanced her dad’s checkbook and helped collect the rent on his properties.She lived with her father, who had served in the Army, and her stepmother and is one of seven siblings. She was keenly focused on academics and would be disappointed if she received a B in a class. She played volleyball in high school, and her family remembers her as being profoundly capable in all things. She helped her dad renovate his dozens of rental properties and could even wire outlets and climb on roofs to tar and repair them.

By all accounts, she was thriving, in overall good health and showing no signs of mental distress beyond the normal teenage growing pains.

“April was a high achiever,” said her older half brother, Guy Burrell. “She was very friendly, very outgoing. She just loved life.”

But in 1995, her family received a nightmarish phone call from one of her professors. April was incoherent and had been hospitalized. The details were hazy, but it appeared that April had suffered a traumatic experience, which The Washington Post isn’t describing to protect her privacy.

After April spent a few months at a short-term psychiatric hospital, she was eventually diagnosed with schizophrenia.

Her family tried their best to take care of her, but April required constant attention, and, in 2000, she went to Pilgrim Psychiatric Center for long-term care. Her family visited as often as they could, making the four-hour drive from Maryland to Long Island once or twice a month. But April was locked in her own world of psychosis, often appearing to draw with her fingers what appeared to be calculations and having conversations with herself about financial transactions.

April was unable to recognize, let alone engage with, her family. She did not want to be touched, hugged or kissed. Her family felt they had lost her.

A promising medical student

When April was diagnosed with schizophrenia, Markx was still a promising medical student, an ocean away at the University of Amsterdam. His parents were both psychiatrists, and he had grown up around psychiatry and its patients. Markx remembers playing as a child in the long-term psychiatric facilities where his parents worked; he was never afraid of the patients or the stigma associated with their illnesses.Sander Markx, the director of precision psychiatry at Columbia University, first met April Burrell when he was a medical student in 2000. (José A. Alvarado Jr. for The Washington Post)

As a visiting Fulbright Scholar to the United States, he made the decision not to head to more well-known institutes, but instead chose Pilgrim Psychiatric Center, a state hospital in Brentwood, N.Y., where many of the state’s most severe psychiatric patients live for months, years or even the rest of their lives.It was during his early days at Pilgrim that he met April, an encounter that “changed everything,” he said.

“She would just stare and just stand there,” Markx said. “She wouldn’t shower, she wouldn’t go outside, she wouldn’t smile, she wouldn’t laugh. And the nursing staff had to physically maneuver her.”

As a student, Markx was not in a position to help her. He moved on with his career but always remembered the young woman frozen at the nurses’ station.

Bringing back April

Almost two decades later, Markx had a lab of his own. He encouraged one of his research fellows to work in the trenches and suggested he spend time with patients at Pilgrim, just as he had done years earlier.In an extraordinary coincidence, the trainee, Anthony Zoghbi, encountered a catatonic patient, standing at the nurses’ desk. The fellow returned to Markx, shaken up, and told him what he had seen.

“It was like déjà vu because he starts telling the story,” said Markx. “And I’m like, ‘Is her name April?’”

Markx was stunned to hear that little had changed for the patient he had seen nearly two decades earlier. In the years since they had first met, April had undergone many courses of treatment — antipsychotics, mood stabilizers and electroconvulsive therapy — all to no avail.

Pilgrim Psychiatric Center in Brentwood, N.Y., in 2016. (Frank Franklin II/AP)

Markx was able to get family consent for a full medical work-up. He convened a multidisciplinary team of more than 70 experts from Columbia and around the world — neuropsychiatrists, neurologists, neuroimmunologists, rheumatologists, medical ethicists — to figure out what was going on.The first conclusive evidence was in her bloodwork: It showed that her immune system was producing copious amounts and types of antibodies that were attacking her body. Brain scans showed evidence that these antibodies were damaging her brain’s temporal lobes, areas that are implicated in schizophrenia and psychosis.

The team hypothesized that these antibodies may have altered the receptors that bind glutamate, an important neurotransmitter, disrupting how neurons can send signals to one another.

Even though April had all the clinical signs of schizophrenia, the team believed that the underlying cause was lupus, a complex autoimmune disorder in which the immune system turns on its own body, producing many antibodies that attack the skin, joints, kidneys or other organs. But April’s symptoms weren’t typical, and there were no obvious external signs of the disease; the lupus appeared to be affecting only her brain.

The autoimmune disease, it seemed, was a specific biological cause — and potential treatment target — for the neuropsychiatric problems April faced. (Whether her earlier trauma had triggered the disease or was unrelated to her condition wasn’t clear.)

The diagnosis made Markx wonder how many other patients like April had been missed and written off as untreatable.

“We don’t know how many of these people are out there,” Markx said. “But we have one person sitting in front of us, and we have to help her.”

Waking up after two decades

The medical team set to work counteracting April’s rampaging immune system and started April on an intensive immunotherapy treatment for neuropsychiatric lupus. Every month for six months, April would receive short, but powerful “pulses” of intravenous steroids for five days, plus a single dose of cyclophosphamide, a heavy-duty immunosuppressive drug typically used in chemotherapy and borrowed from the field of oncology. She was also treated with rituximab, a drug initially developed for lymphoma.The regimen is grueling, requiring a month-long break between each of the six rounds to allow the immune system to recover. But April started showing signs of improvement almost immediately.

As part of a standard cognitive test known as the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA), she was asked to draw a clock — a common way to assess cognitive impairment. Before the treatment, she tested at the level of a dementia patient, drawing indecipherable scribbles.

But within the first two rounds of treatment, she was able to draw half a clock — as if one half of her brain was coming back online, Markx said.

Following the third round of treatment a month later, the clock looked almost perfect.

Drawing a clock is a common way to assess cognitive impairment. These clocks, drawn by April, show how significantly the treatment regimen was helping her. (Courtesy of Sander Markx)

Despite this improvement, her psychosis remained. As a result, some members of the team wanted to transfer April back to Pilgrim Psychiatric Center, Markx said. At the time, Markx had to travel home to the Netherlands, and he feared that in his absence, April would be returned to Pilgrim.

On the day Markx was scheduled to fly out, he entered the hospital one last time to check on his patient, whom he typically found sitting in the dining room in her catatonic state.

But when Markx walked in, April didn’t seem to be there. Instead, he saw another woman sitting in the room.

“It didn’t look like the person I had known for 20 years and had seen so impaired,” Markx said. “And then I look a little closer, and I’m like, ‘Holy s---. It’s her.’”

It was as if April had awakened after more than 20 years.

A joyful reunion

“I’ve always wanted my sister to get back to who she was,” Guy Burrell said.In 2020, April was deemed mentally competent to discharge herself from the psychiatric hospital where she had lived for nearly two decades, and she moved to a rehabilitation center.

Because of visiting restrictions related to covid, the family’s face-to-face reunion with April was delayed until last year. April’s brother, sister-in-law and their kids were finally able to visit her at a rehabilitation center, and the occasion was tearful and joyous.

“... she recalled her childhood home in Baltimore, the grades she got in school, being a bridesmaid in her brother’s wedding — seemingly everything up until when the autoimmune inflammatory processes began affecting her brain.”

“When she came in there, you would’ve thought she was a brand-new person,” Guy Burrell said. “She knew all of us, remembered different stuff from back when she was a child.”A video of the reunion shows that April was still tentative and fragile. But her family said she remembered her childhood home in Baltimore, the grades she got in school, being a bridesmaid in her brother’s wedding — seemingly everything up until when the autoimmune inflammatory processes began affecting her brain. She even recognized her niece, whom April had only seen as a small child, now a grown young woman. When her father hopped on a video call, April remarked “Oh, you lost your hair,” and burst out laughing, Guy Burrell recalled.

The family felt as if they’d witnessed a miracle.

“She was hugging me, she was holding my hand,” Guy Burrell said. “You might as well have thrown a parade because we were so happy, because we hadn’t seen her like that in, like, forever.”

“It was like she came home,” Markx said. “We never thought that was possible.”

Finding more forgotten patients

Markx talked about how, as a teenager, he saw the movie adaptation of Oliver Sacks’s “Awakenings,” featuring Robin Williams and Robert DeNiro, and how it had haunted him. “The notion that people are gone in these mental institutes and that they come back still, that has always stuck with me,” he said.Before his death in 2015, Sacks had spoken to Markx about the discoveries involving patients like April. Sacks, also a professor at Columbia University, had a personal interest in the work. He had a brother with schizophrenia.

“Your work gives me hope about the outcomes we can achieve with our patients that I never before would have dreamed possible, as these are true cases of ‘Awakenings’ where people get to go back home to their families to live out their lives,” Sacks said, according to contemporaneous notes kept by Markx. (The statement was confirmed by Kate Edgar, Sacks’s long-term personal editor and executive director of the Oliver Sacks Foundation.)

After April’s unexpected recovery, the medical team put out an alert to the hospital system to identify any patients with antibody markers for autoimmune disease. A few months later, Anca Askanase, a rheumatologist and director of the Columbia Lupus Center, who had been on April’s treatment team, approached Markx. “I think we found our girl,” she said.

Bringing back Devine

When Devine Cruz was 9, she began to hear voices. At first, the voices fought with one another. But as she grew older, the voices would talk about her. One night, the voices urged her to kill herself.For more than a decade, the young woman moved in and out of hospitals for treatment. Her symptoms included visual and auditory hallucinations, as well as delusions that prevented her from living a normal life.

Devine was eventually diagnosed with schizoaffective disorder, which can result in symptoms of both schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. She also was diagnosed with intellectual disability.

She was on a laundry list of drugs — two antipsychotic medications, lithium, clonazepam, Ativan and benztropine — that came with a litany of side effects but didn’t resolve all her symptoms. She was often unaware of what was going on; her hair was disheveled, and her medications caused her to shake and drool, her doctors said.

She also had lupus, which she had been diagnosed with when she was about 14, although doctors had never made a connection between the disease and her mental health.

When Markx and his team found Devine, she was 20 and held the adamant delusion that she was pregnant despite multiple negative pregnancy tests.

“That’s when she was probably at her worst,” said Sophia Chaudry, a precision psychiatry fellow at Columbia University Medical Center and physician who was closely involved in Devine’s care.

Last August, the medical team prescribed monthly immunosuppressive infusions of corticosteroids and chemotherapy drugs, a regime similar to what April had been given a few years prior. By October, there were already dramatic signs of improvement.

“She was like ‘Yeah, I gotta go,’” Markx said. “‘Like, I’ve been missing out.’”

After several treatments, Devine began developing awareness that the voices in her head were different from real voices, a sign that she was reconnecting with reality. She finished her sixth and final round of infusions in January.

In March, she was well enough to meet with a reporter. “I feel like I’m already better,” Devine said during a conversation in Markx’s office at the New York State Psychiatric Institute, where she was treated. “I feel myself being a person that I was supposed to be my whole entire life.”

Her presence during the interview was at first timid and childlike. She said her excitement and anxiety about discussing her story reminded her of how she felt in school the day before a big field trip.

Although she had lost about 10 years of her life to her illness, she remembers many details. As a child, she did not know how to explain what she was going through to her family and often isolated herself in her room.

“Because the crisis was so bad, it felt like I was being mute,” Devine said. “I was talking without making any sense, so they wouldn’t understand what I was saying.”

Devine still remembers what the voices sounded like and the often disturbing images she hallucinated: a hand reaching down from the ceiling as she lay in bed, the creepy nurse with the crooked head and black teeth who approached her in the hospital.

She remembers the paranoia she felt at times. “I thought that the world was ending; I thought that the police were out to get me.”

But she also remembers that fateful first phone call with Markx when she learned that her lupus could be affecting her brain. She remembers asking, “If it affects my brain, what does this have to do with my mental illness?”

Her recovery is remarkable for several reasons, her doctors said. The voices and visions have stopped. And she no longer meets the diagnostic criteria for either schizoaffective disorder or intellectual disability, Markx said.

In a recent neuropsychiatric evaluation, Devine not only drew a perfect clock, but also asked how the physician was doing, a level of engagement that the doctor found so surprising that she noted it in the patient report.

Sophia Chaudry, a doctor in Markx's lab, was assigned to Devine’s care and accompanied Devine to her treatments when her family wasn’t available. (José A. Alvarado Jr. for The Washington Post)

But more importantly, Devine now recognizes that her previous delusions weren’t real. Such awareness is profound because many severely sick mental health patients never reach that understanding, Chaudry said.Today, Devine lives with her mother and is leading a more active and engaged life. She helps her mother cook, goes to the grocery store and navigates public transportation to keep her appointments. She is even babysitting her siblings’ young children — listening to music, taking them to the park or watching “Frozen 2” — responsibilities her family never would have entrusted her with before her recovery.

She is grateful for her treatment and the team that made it possible. “Without their help, I wouldn’t be here,” Devine said.

“I feel more excited,” she said. “Like a new chapter is beginning.”

Expanding the search for more patients

While it is likely that only a subset of people diagnosed with schizophrenia and psychotic disorders have an underlying autoimmune condition, Markx and other doctors believe there are probably many more patients whose psychiatric conditions are caused or exacerbated by autoimmune issues.The cases of April and Devine also helped inspire the development of the SNF Center for Precision Psychiatry and Mental Health at Columbia, which was named for the Stavros Niarchos Foundation, which awarded it a $75 million grant in April. The goal of the center is to develop new treatments based on specific genetic and autoimmune causes of psychiatric illness, said Joseph Gogos, co-director of the SNF Center.

Markx said he has begun care and treatment on about 40 patients since the SNF Center opened. The SNF Center is working with the New York State Office of Mental Health, which oversees one of the largest public mental health systems in America, to conduct whole genome sequencing and autoimmunity screening on inpatients at long-term facilities.

For “the most disabled, the sickest of the sick, even if we can help just a small fraction of them, by doing these detailed analyses, that’s worth something,” said Thomas Smith, chief medical officer for the New York State Office of Mental Health. “You’re helping save someone’s life, get them out of the hospital, have them live in the community, go home.”

Discussions are underway to extend the search to the 20,000 outpatients in the New York state system as well. Serious psychiatric disorders, like schizophrenia, are more likely to be undertreated in underprivileged groups. And autoimmune disorders like lupus disproportionately affect women and people of color with more severity.

Changing psychiatric care

How many people ultimately will be helped by the research remains a subject of debate in the scientific community. But the research has spurred excitement about the potential to better understand what is going on in the brain during serious mental illness.“I think we, as basic neuroscientists, are now in a position, both conceptually and technologically, to contribute, and it’s our responsibility to do so,” said Richard Axel, Nobel laureate and co-director of Columbia’s Zuckerman Mind Brain Behavior Institute.

Emerging research has implicated inflammation and immunological dysfunction as potential players in a variety of neuropsychiatric conditions, including schizophrenia, depression and autism.

“It opens new treatment possibilities to patients that used to be treated very differently,” said Ludger Tebartz van Elst, a professor of psychiatry and psychotherapy at University Medical Clinic Freiburg in Germany.

In one study, published last year in Molecular Psychiatry, Tebartz van Elst and his colleagues identified 91 psychiatric patients with suspected autoimmune diseases, and reported that immunotherapies benefited the majority of them.

Belinda Lennox, head of the psychiatry department at the University of Oxford, is enrolling patients in clinical trials to test the effectiveness of immunotherapy for autoimmune psychosis patients.

In addition to more common autoimmune conditions, researchers also have identified 17 diseases, many with different neurological and psychiatric symptoms, in which antibodies specifically target neurons, said Josep Dalmau, a neurologist at the University of Barcelona Hospital Clinic. Dalmau first identified one of the most common of these diseases, called anti-NMDA receptor autoimmune encephalitis.

As a result of the research, screenings for immunological markers in psychotic patients are already routine in Germany, where psychiatrists regularly collect samples from cerebrospinal fluid.

Markx is also doing similar screening with his patients. He believes highly sensitive and inexpensive blood tests to detect different antibodies should become part of the standard screening protocol for psychosis.

“I think we’re at the dawn of a new era. This is just the beginning,” said Yancopoulos.

In June, Markx will present the findings at a conference organized by the Stavros Niarchos Foundation.

And Devine will be there to share her story in her own words...

Model Letter to Prolife Legislators

https://www.respectforhumanlife.com/

Dr. Heidi Klessig & Christopher Bogosh RN May 11 4 min read Updated: May 30We thought it would be helpful to put together the body of a model letter to cut and paste to send to prolife legislators (here is an example) or to anyone to serve as informed consent regarding the risks of registering as an organ donor. The material in this model letter was created after extensive research and in collaboration with several prolife medical professionals. Please feel free to copy, reproduce, and disseminate.

******

While the abortion issue is significant for prolife advocates, another form of disrespect for human life occurs in our nation’s hospitals every day due to the Uniform Determination of Death Act (UDDA) and now a recent push to loosen the UDDA death by neurological criteria (DNC) standards further (rUDDA). The UDDA is a legal fiction that declares people dead while they still have biological signs of life, and it exploits registered non-responsive organ donors who experienced a head injury. These altruistic people never receive informed consent regarding the potential risks of being a registered organ donor.

The UDDA became law in 1981, and it permits a definition of death to allow the harvesting of organs from still-living donors with impaired brain function on a ventilator who do not meet the Dead Donor Rule (DDR). The public has not been informed that a person declared dead by neurological criteria (DNC), i.e., allegedly “brain dead,” still has a heart beating on its own, circulation, and respiration (exchange of oxygen and carbon dioxide in the tissues). Also, many people declared dead under the UDDA whole-brain standard (DNC) still have a functioning hypothalamus, an essential part of the brain that interacts with the body. Several people have also recovered after a diagnosis of brain death and went on to live regular lives.

Other signs of life also continue in those meeting the DNC standard, such as wound healing, a complicated diffuse process throughout the body of many factors circulating in the blood and interacting with cells, tissues, and organs. There is urine production, temperature maintenance, and homeostasis of interdependently functioning organs and systems. If a “brain-dead” woman is pregnant, she can carry and nourish the baby in her womb. Not to mention, DNC organ donors undergoing harvest surgeries require the presence of an anesthesiologist to manage increases in heart rate and blood pressure, which are more than reflex responses, as well as other objective signs of suffering in response to the cutting of flesh and sawing of bone.

What was mentioned above does not occur in people who experience natural death. Physicians may refer to the person declared dead using the DNC criteria as a corpse, but he or she still has signs of life, unlike an actual corpse ready for the morgue. Considering all of this, it is now a well-established fact amongst medical professionals that the UDDA is a legal fiction, and organ donors declared dead under the UDDA whole-brain criteria violate the DDR—their demise occurs through the removal of their organs.

The UDDA and hospitals in our nation do not respect the lives of organ donors with impaired brain function on ventilators, who never received informed consent about the risks of registering to donate their organs.

The organ transplant stakeholders would have the public believe that if medical intervention is stopped in organ donors meeting DNC criteria, natural death will occur instantly, but this is not the case. After withdrawing from a ventilator, these people may continue to live for minutes, hours, days, months, and even years with non-aggressive medical and nursing care. Not to mention those already referenced who completely recovered after they were declared “brain dead,” which indicates the fallibility of diagnostic testing and expert opinion (see Covert Consciousness, Cognitive Bias, and Medical Hubris). Of course, if organ donors experience natural death, their hearts, lungs, livers, kidneys, and other vital organs will no longer be suitable for transplant. Other utilitarian and capitalistic factors motivate Organ Procurement Organizations (OPOs), hospitals that perform transplant surgeries, and transplant surgeons.

At this point, the organ procurement issue is like abortion because judgment is passed on human life. The result: a person is put to death, and his or her still-living biological parts are used for the “betterment of society” as a whole. Whether they are aborted fetal cells from the 1970s kept in labs to manufacture COVID-19 shots; or the heart, lungs, liver, and kidneys of a newly licensed organ donor involved in a car accident that are transplanted into five people deemed more worthy of ongoing life—both abortion and the current organ procurement practice reflect the “Life Unworthy of Life” doctrine of Nazi Germany.

Since the Uniform Law Commission (ULC) is presently working with organ procurement stakeholders to loosen the UDDA criteria further, I urge you to introduce legislation to repeal the UDDA and suggest the following replacement:

No one shall be declared dead unless the respiratory and circulatory systems and the entire brain have been destroyed. Such destruction shall be determined in accordance with universally accepted medical standards.

We must respect life in every stage, from conception until natural death.

Premature declaration of death still happens, even in Equador, "ranked in the global top 50 for efficiency, based on government spending and life expectancy, according to the Bloomberg Health-Efficiency Index."

Maybe Michigan is trying to catch up with that efficiency. Did you know state bills dramatically changed local procedures for determining cause of death last year, giving MDHHS final authority? I cover these bills and more in the upcoming book, MHF Guide to State Health Policy.

https://www.nbcnews.com/news/world/woman-declared-dead-revives-wake-bangs-coffin-ecuador-rcna88992

“It gave us all a fright,” said the woman's son.June 13, 2023, 5:47 AM EDT

By Alexander Smith

Mourners in Ecuador had gathered at the funeral of retired nurse Bella Montoya when they heard strange noises coming from inside the coffin.That might sound like a trope from a horror movie, but relatives were startled to see that Montoya — who had been declared dead after she was believed to have suffered a stroke and cardiac arrest — was still alive and breathing, her family and officials said Monday.

“It gave us all a fright,” her son, Gilberto Barbera, told The Associated Press.

The woman, 76, was unconscious when her family took her to the hospital in the central city of Babahoyo on Friday, her son told the AP.

She did not respond to resuscitation, and the doctor on duty at Hospital Martín Icaza de Babahoyo declared that she had died, the Ecuadorian health ministry said in a statement.

Her family took her to the funeral home the same day, only to hear sounds from inside her coffin during the wake, her son said.

“There were about 20 of us there,” he said. “After about five hours of the wake, the coffin started to make sounds. My mom was wrapped in sheets and hitting the coffin, and when we approached we could see that she was breathing heavily.”

Dead woman revives during her own wake in Ecuador.

Bella Montoya, 76, seemingly revived inside her coffin. AP

Video recorded immediately afterward showed a coffin resting on the floor of a small, bare, light-blue room furnished with a silver crucifix and a pedestal fan. Inside the open casket was a woman with a gaunt face and gray hair, who was moving her mouth up and down as two men supported her head.She was rushed back to the hospital, where she remained intubated in intensive care, the health ministry said, describing her condition as “unstable.” Her son said doctors had not given them much hope about her prognosis.

The health ministry said it has formed a committee with other government agencies to audit how the premature declaration of death came about.

Ecuador's public health care system provides universal coverage.

Even though Ecuador is a middle-income nation, its health care system is ranked in the global top 50 for efficiency, based on government spending and life expectancy, according to the Bloomberg Health-Efficiency Index.

After the incident Friday, the health ministry tried to reassure Ecuadorians that it “maintains the offer of health services to the population at all levels of care.”

CORRECTION (June 13, 2023, 7:30 p.m. ET): A previous version of this article misspelled part of the name of the hospital where Bella Montoya was mistakenly declared dead. It is Hospital Martín Icaza de Babahoyo, not Marlin.

Recently in Michigan, a college student died, an apparent homicide. An initial report described the procedure before her organs were harvested.

She was taken to nearby Ascension Providence Hospital, where she stayed on life support for two days, her mother said. She was pronounced dead on June 5, but put back on life support until June 8...

A follow-up report continued to raise questions about the nature of her injuries.

What Happened To Mia Kanu? HBCU Student Dies After Being Found On Michigan Road Following Party

By NewsOne Staff, 3 days ago [June 16, 2023]CORRECTION: A previous version of this article misspelled Mia Kanu’s last name. This article has been updated to reflect a correction.

T he family of an aspiring veterinarian and student at a historically Black college (HBCU) is demanding answers after she died days after being found in the middle of a road in Michigan following a party earlier this month.

Mia Kanu either fell out of a moving car or was pushed from one, police deduced after viewing surveillance video that recorded footage of the 23-year-old landing on a road in suburban Detroit in the early morning hours of June 2. But that is seemingly the extent of the information Kanu’s family and local law enforcement said they have amid an investigation that is being treated as a homicide case.

Kanu, who returned to her family’s home in Southfield while on summer break from Tennessee State University (TSU), was hospitalized and placed on life support for several days before she was pronounced dead on June 5, according to the Detroit Free Press.

The nature of Kanu’s injury is uncertain, but Click on Detroit reported she suffered “a serious injury to the back of her head.”

She had been attending a party with her friends before she was found, but little else is known beyond that, her mother said.

“I don’t know what happened,” Bianca Vanmeter told the Detroit Free Press.

Kanu was an organ donor. Her liver went to a baby in need and her kidneys went to someone else.

“We really wanted her heart to go to somebody, because she had such a big heart, but she had a very rare blood type, so we couldn’t find anybody for that,” Kanu’s mother said.

Kanu was hesitant to leave TSU for the summer because of her job at a local veterinarian’s office, her mother said.

“She loved it there (at TSU),” Vanmeter told the Detroit Free Press. “She was already counting the days for when she could go back to school.”

A GoFundMe account set up for Kanu has already garnered more than $33,000 of its $50,000 goal.

“Mia dedicated her life to her family and her friends,” the GoFundMe said in part. “She was so kind, loving, sweet and funny. She was always a team leader and very active in volleyball and school activities. Mia was on track to be a veterinarian until her dreams were cut short.”

The donations will be used to “ease financial burdens” with Kanu’s funeral and memorial as well as to “ help her family get through this difficult time.”

NewsOne extends condolences to Kanu’s family, friends and loved ones.

Wouldn't you know monopoly would be behind the UNOS system sloppiness - and worse?

Patients have known things weren't right.

The recent US Senate hearing exposes the dark underbelly. Report by MedPage Today.

https://www.medpagetoday.com/transplantation/transplantation/

Experts Demand Overhaul of Organ Transplant System During Senate Hearing

— Patient representative has "zero confidence" in change if UNOS remains involved

Patients, advocates, and one rogue organ procurement organization (OPO) executive, among others, pledged support for legislation that aims to disrupt a decades-long monopoly over the U.S. transplant system during a hearingopens in a new tab or window of the Senate Finance Subcommittee on Health Care on Thursday.

"Every day 17 people die while on organ transplant waiting lists and another 13 are removed from the waiting list because they've become too sick to receive a transplant," said Sen. Todd Young (R-Ind.)

LaQuayia Goldring is one of the more than 100,000 people on that list. At age 3, Wilms tumor, a rare kidney cancer, took over Goldring's left kidney. She went into kidney failure and received her first transplant when she was 17. By the time she was 25, she was back in kidney failure.

She has waited "9 agonizing years" for a transplant and is now dependent on dialysis 5 days a week.

Just a few weeks ago, a donor family reached out to Goldring having chosen her for a kidney transplant, but because of a glitch in the United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS) system, her status was listed as "inactive," she said. She contacted them and was told this was due to a "clerical error."

This was not a one-time error, Goldring noted.

"UNOS technology is unsecure and unreliable and it crashes hourly and, during that time, transplant candidates are not getting phone calls," she said. "Every time this happens, patients like me continue to die."

In addition to these technology problems, in 2020 a Senate Finance Committee investigation uncovered other significant failures of the organ transplant system, including errors in testing and transportation, misuse of Medicare funds, and UNOS's lack of oversight, said Subcommittee Chair Ben Cardin (D-Md.)

At an August 2022 Senate Finance Committee hearingopens in a new tab or window, witnesses described organs delivered in boxes with tire treads or left rotting at airports, and the committee's investigation uncovered hundreds of organ recipients who contracted diseases because of lax screening.

Instead of acknowledging their shortcomings, UNOS has attempted to hide its mistakes, citing "alleged record increases in organ donation," said Sen. Chuck Grassley (R-Iowa). In reality, these increases are the result of "public health tragedies," including the opioid epidemic, and not an indicator of UNOS's performance.

Molly McCarthy, vice chair of the Patient Affairs Committee for the Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network (OPTN) -- and a three-time transplant recipient -- had a front-row seat observing the "gross negligence and abuse" of the government's own contractors.

She reaffirmed Grassley's statements, citing "systematic efforts to misrepresent the facts" by leveraging the opioid epidemic, gun violence deaths, and suicides as evidence of their own achievements.

"All UNOS is celebrating are national tragedies, not evidence of a well-run system," McCarthy said. "What I have observed is that UNOS, at best, treats patients as props. At worst, it outright lies to us, and then uses us as a shield against much-needed oversight and reform. Now, UNOS knows enough not to lie to Congress. So, it lies to its patients instead and then launders those lies through us."

"I have zero confidence that we will ever see improvement if UNOS has any role whatsoever in the transplant system," she added.

Matthew Wadsworth, president and CEO of Life Connection of Ohio, an OPO that manages organ donation in Northwest and West Central Ohio, agreed with McCarthy -- but reserved some blame for CMS.

"The current system is broken," he said. "There are absolutely no guardrails in place to ensure that OPOs are adequately serving patients and many of them aren't."

Because of geographic monopolies, many have become "complacent," even "sluggish," and yet there are no consequences for their poor performance, he noted, adding that CMS has never de-certified an OPO.

In 2020, the agency issued a new OPO rule for the first time in 40 years. However, 3 years later it has yet to say how it will enforce its rule. Additionally, the agency has yet to take action to close a "dangerous loophole" that gives OPOs credit for procuring pancreata that aren't transplanted and instead used for research.

"This means that OPOs that are failing at their central task -- recovering organs for transplant -- can avoid accountability by simply recovering one organ and labeling it research," he said.

In the decades since the National Organ Transplant Act (NOTA) of 1984, the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) awarded the OPTN contract for the network to only one entity: UNOS.

One reason for these repeat contracts is that NOTA only allowed HHS to contract with a "non-profit entity with expertise in organ procurement and transplantation," and has been interpreted as prohibiting the agency from seeking bids from public and private entities that might more effectively manage these contracts.

A new bill, the Securing the U.S. Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network Actopens in a new tab or window, seeks to break up the organ transplant monopoly by giving HRSA the ability, for the first time, to engage in a competitive process of awarding the OPTN contract.

Wadsworth urged Congress to pass this bill and allow patients to be served by high-performing groups across technology, logistics, data analytics, and other areas critical to improving system performance.

He also called on Congress to "prepare to enforce the OPO rule, without weakening or delaying it, including closing the pancreas-for-research loophole, publishing guidance on how the rule is going to be enforced, and requiring the publication of OPO process data."

Congress also needs to eliminate conflicts of interest that discourage OPOs from investing their resources in areas that grow donation and transplantation, he said.

UNOS issued a press releaseopens in a new tab or window on Thursday underscoring its "commitment to modernizing and reforming the nation's organ donation and transplant system and working with Congress to achieve measurable results for patients."

"Patients and families are counting on us to pursue improvements that increase transparency, strengthen accountability, and save more lives. We support calls for patient-focused improvements and want to be part of the solution," said UNOS CEO Maureen McBride, PhD.

Get past a few racist tropes, and NBC News reports federal plans everyone should know.

Personally, I think competition for UNOS is a great way to address inefficiency and terribly poor customer service.

U.S. plans major revamp of troubled organ transplant system

Seventeen people die every day waiting for organ transplants in the U.S.The federal government Wednesday outlined a plan to revamp the nation's organ transplant system, which has been plagued by problems, including damaged or discarded organs and long wait times.

Around 104,000 people in the United States are on the waiting list for an organ transplant, according to the Health Resources and Services Administration, an agency within the Department of Health and Human Services. Seventeen people die each day waiting for an organ transplant.

The current system, experts say, is ineffective and usually benefits affluent white people who have the means to travel where organs are available.

"There are multiple problems that need to be addressed," said Dr. Stuart Knechtle, a general surgeon at the Duke University School of Medicine in Durham, North Carolina. “It’s clear that different groups of people by race and also by geographic location are served differently."

People involved in the system have been trying to make improvements for over a decade, Dr. David Mulligan, a transplant surgeon and immunologist in the Department of Surgery at Yale School of Medicine in New Haven, Connecticut, said in an interview.

"We've got to be able to get organs from donors to recipients in a more fluid, efficient way," he said.

The plan — outlined by HRSA in a release — would nearly double the amount of funding the government agency receives from the U.S. to $67 million in the fiscal year 2024 to "modernize" the nation's transplant system.

The current system is outdated, based on a model from the 1980s, Knechtle said. A new program would provide patients with more timely information, empowering them to take more control over the transplant journey, he said. It would also help address equity issues, where people who should be referred for a transplant are overlooked or given access to care too late.

The U.S. government would also siphon away some of the responsibilities performed by the United Network for Organ Sharing, more commonly referred to as UNOS, to other outside organizations.

UNOS, a nonprofit organization based in Richmond, Virginia, has been the sole manager of the nation’s organ transplant system since 1986, when the federal government awarded the group a contract. The group has essentially operated as a monopoly, overseeing the system that gets donated organs to seriously ill patients.

The group has been blamed by U.S. lawmakers and other outside groups for not adequately managing the nation's transplant and organ procurement centers, which has resulted in damaged organs and delays that led to unsuccessful transplants, Mulligan said, adding that he thinks some of the critiques are unfair. Mulligan is a former president of UNOS.

UNOS did not immediately reply to a request for comment.

The government's plan would also create an independent board of directors as well as produce an online dashboard that would give the public more information, including on organ retrieval, waitlist outcomes and demographic data on recipients.

The moves would create "transparency and accountability in the system," Carole Johnson, the administrator for HRSA, said in a statement.

“Every day, patients and families across the United States rely on the Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network to save the lives of their loved ones who experience organ failure,” Johnson said.

There's no set timeframe for when the changes will be implemented, Johnson suggested in an interview, noting the agency is approaching the revamp very "thoughtfully."

Knechtle said he was "eager" for changes.

"I think there's been a great deal of criticism of the system. And we agree with those criticisms," he said.

In January, UNOS proposed its own series of reforms for improving the organ transplant system, including creating new tools that would help patients better navigate the donation and transplant process.